Which Of The Following Help Readers Draw Conclusions Or Support Business Decisions?

Learning Objectives

- Describe the role of random sampling and random assignment in drawing cause-and-outcome conclusions

Generalizability

Effigy ane. Generalizability is an important research consideration: The results of studies with widely representative samples are more than likely to generalize to the population. [Image: Barnacles Budget Accommodation]

I limitation to the study mentioned previously about the babies choosing the "helper" toy is that the determination only applies to the 16 infants in the study. We don't know much nigh how those xvi infants were selected. Suppose we want to select a subset of individuals (a sample) from a much larger group of individuals (the population) in such a style that conclusions from the sample can be generalized to the larger population. This is the question faced past pollsters every day.

Case 1: The General Social Survey (GSS) is a survey on societal trends conducted every other year in the Usa. Based on a sample of nigh ii,000 adult Americans, researchers make claims virtually what pct of the U.Southward. population consider themselves to exist "liberal," what percentage consider themselves "happy," what percentage feel "rushed" in their daily lives, and many other issues. The key to making these claims about the larger population of all American adults lies in how the sample is selected. The goal is to select a sample that is representative of the population, and a common mode to accomplish this goal is to select a random sample that gives every member of the population an equal chance of being selected for the sample. In its simplest form, random sampling involves numbering every member of the population and then using a computer to randomly select the subset to be surveyed. Most polls don't operate exactly like this, but they do apply probability-based sampling methods to select individuals from nationally representative panels.

In 2004, the GSS reported that 817 of 977 respondents (or 83.half-dozen%) indicated that they always or sometimes feel rushed. This is a clear majority, but nosotros again need to consider variation due to random sampling. Fortunately, we tin use the same probability model nosotros did in the previous example to investigate the likely size of this mistake. (Note, we tin can use the coin-tossing model when the actual population size is much, much larger than the sample size, as then we can still consider the probability to exist the aforementioned for every private in the sample.) This probability model predicts that the sample result will be within 3 pct points of the population value (roughly 1 over the foursquare root of the sample size, the margin of error). A statistician would conclude, with 95% confidence, that between 80.half dozen% and 86.half dozen% of all adult Americans in 2004 would take responded that they sometimes or always feel rushed.

The key to the margin of error is that when we use a probability sampling method, nosotros tin make claims well-nigh how often (in the long run, with repeated random sampling) the sample result would fall within a certain distance from the unknown population value by chance (meaning by random sampling variation) alone. Conversely, not-random samples are often suspect to bias, pregnant the sampling method systematically over-represents some segments of the population and under-represents others. Nosotros also however need to consider other sources of bias, such as individuals not responding honestly. These sources of error are not measured by the margin of mistake.

Endeavor It

Cause and Event

In many research studies, the principal question of interest concerns differences betwixt groups. Then the question becomes how were the groups formed (e.k., selecting people who already drink java vs. those who don't). In some studies, the researchers actively form the groups themselves. Just then nosotros accept a like question—could whatever differences nosotros observe in the groups exist an artifact of that grouping-formation process? Or maybe the difference we observe in the groups is so large that nosotros can discount a "fluke" in the grouping-formation process as a reasonable explanation for what nosotros find?

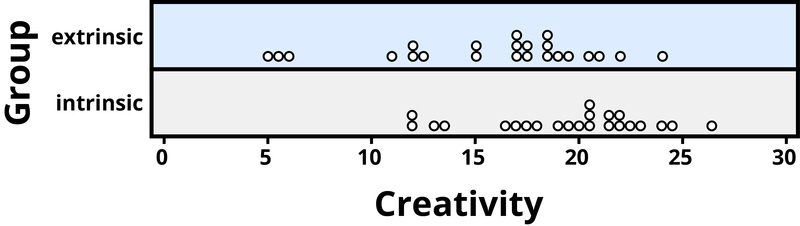

Example 2: A psychology study investigated whether people tend to display more than inventiveness when they are thinking about intrinsic (internal) or extrinsic (external) motivations (Ramsey & Schafer, 2002, based on a study by Amabile, 1985). The subjects were 47 people with extensive experience with artistic writing. Subjects began by answering survey questions about either intrinsic motivations for writing (such equally the pleasure of self-expression) or extrinsic motivations (such as public recognition). And then all subjects were instructed to write a haiku, and those poems were evaluated for creativity by a panel of judges. The researchers conjectured beforehand that subjects who were thinking about intrinsic motivations would brandish more than inventiveness than subjects who were thinking about extrinsic motivations. The creativity scores from the 47 subjects in this written report are displayed in Effigy 2, where higher scores indicate more than inventiveness.

Figure two. Creativity scores separated past blazon of motivation.

In this example, the fundamental question is whether the type of motivation affects creativity scores. In particular, do subjects who were asked about intrinsic motivations tend to have college creativity scores than subjects who were asked well-nigh extrinsic motivations?

Effigy ii reveals that both motivation groups saw considerable variability in inventiveness scores, and these scores have considerable overlap between the groups. In other words, it's certainly not ever the case that those with extrinsic motivations have higher creativity than those with intrinsic motivations, but at that place may even so be a statistical tendency in this direction. (Psychologist Keith Stanovich (2013) refers to people's difficulties with thinking virtually such probabilistic tendencies equally "the Achilles heel of homo cognition.")

The mean inventiveness score is 19.88 for the intrinsic group, compared to xv.74 for the extrinsic group, which supports the researchers' conjecture. All the same comparing only the means of the ii groups fails to consider the variability of creativity scores in the groups. We can measure variability with statistics using, for case, the standard deviation: v.25 for the extrinsic grouping and 4.twoscore for the intrinsic group. The standard deviations tell us that almost of the creativity scores are within about five points of the hateful score in each group. We see that the mean score for the intrinsic grouping lies within one standard difference of the hateful score for extrinsic group. And then, although there is a trend for the inventiveness scores to be higher in the intrinsic group, on average, the departure is not extremely big.

Nosotros again desire to consider possible explanations for this difference. The study just involved individuals with extensive creative writing experience. Although this limits the population to which nosotros can generalize, it does not explain why the hateful creativity score was a bit larger for the intrinsic grouping than for the extrinsic group. Maybe women tend to receive higher creativity scores? Hither is where we demand to focus on how the individuals were assigned to the motivation groups. If only women were in the intrinsic motivation group and only men in the extrinsic group, then this would present a trouble considering nosotros wouldn't know if the intrinsic group did amend because of the dissimilar type of motivation or because they were women. Yet, the researchers guarded confronting such a problem past randomly assigning the individuals to the motivation groups. Like flipping a coin, each individual was just as probable to be assigned to either type of motivation. Why is this helpful? Because this random assignment tends to rest out all the variables related to creativity we tin recollect of, and even those we don't remember of in advance, between the two groups. So we should have a like male person/female split between the two groups; we should have a similar historic period distribution between the two groups; nosotros should have a similar distribution of educational background between the two groups; and then on. Random assignment should produce groups that are as similar as possible except for the type of motivation, which presumably eliminates all those other variables as possible explanations for the observed tendency for higher scores in the intrinsic group.

But does this e'er work? No, so past "luck of the draw" the groups may exist a little different prior to answering the motivation survey. And then then the question is, is information technology possible that an unlucky random assignment is responsible for the observed difference in creativity scores between the groups? In other words, suppose each individual's poem was going to get the aforementioned inventiveness score no matter which group they were assigned to, that the type of motivation in no way impacted their score. Then how oftentimes would the random-assignment process lonely pb to a departure in mean creativity scores as large (or larger) than 19.88 – fifteen.74 = 4.14 points?

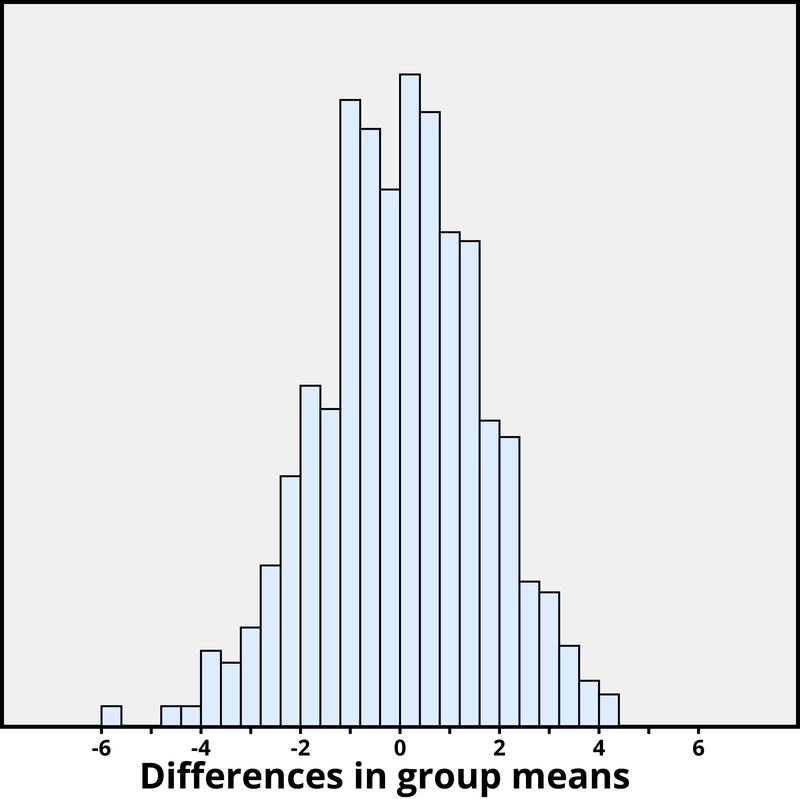

We again want to apply to a probability model to gauge a p-value, only this time the model will be a bit different. Think of writing everyone's creativity scores on an index carte du jour, shuffling up the index cards, and then dealing out 23 to the extrinsic motivation group and 24 to the intrinsic motivation group, and finding the divergence in the grouping means. We (ameliorate yet, the estimator) tin repeat this procedure over and over to run into how oft, when the scores don't modify, random assignment leads to a difference in means at least every bit big equally 4.41. Figure iii shows the results from 1,000 such hypothetical random assignments for these scores.

Figure 3. Differences in group means under random assignment alone.

Only 2 of the 1,000 simulated random assignments produced a divergence in group ways of 4.41 or larger. In other words, the approximate p-value is 2/1000 = 0.002. This small p-value indicates that it would be very surprising for the random assignment process lonely to produce such a big departure in group means. Therefore, as with Instance two, we have strong show that focusing on intrinsic motivations tends to increment inventiveness scores, as compared to thinking almost extrinsic motivations.

Notice that the previous statement implies a cause-and-issue relationship between motivation and creativity score; is such a strong conclusion justified? Yes, considering of the random assignment used in the study. That should have balanced out whatever other variables between the ii groups, so now that the small-scale p-value convinces us that the higher mean in the intrinsic group wasn't just a coincidence, the only reasonable caption left is the departure in the type of motivation. Tin nosotros generalize this decision to everyone? Not necessarily—we could charily generalize this conclusion to individuals with extensive experience in creative writing similar the individuals in this written report, simply we would still desire to know more than about how these individuals were selected to participate.

Conclusion

Figure 4. Researchers employ the scientific method that involves a great deal of statistical thinking: generate a hypothesis –> design a study to examination that hypothesis –> conduct the study –> analyze the data –> study the results. [Image: widdowquinn]

Statistical thinking involves the careful pattern of a report to collect meaningful data to answer a focused research question, detailed analysis of patterns in the data, and cartoon conclusions that become across the observed data. Random sampling is paramount to generalizing results from our sample to a larger population, and random assignment is fundamental to drawing cause-and-result conclusions. With both kinds of randomness, probability models aid us assess how much random variation we can expect in our results, in lodge to determine whether our results could happen by gamble lone and to estimate a margin of fault.

And so where does this exit us with regard to the coffee study mentioned previously (the Freedman, Park, Abnet, Hollenbeck, & Sinha, 2012 institute that men who drank at least six cups of coffee a day had a ten% lower chance of dying (women 15% lower) than those who drank none)? Nosotros can reply many of the questions:

- This was a 14-yr study conducted past researchers at the National Cancer Found.

- The results were published in the June issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, a respected, peer-reviewed journal.

- The study reviewed coffee habits of more than than 402,000 people ages fifty to 71 from six states and two metropolitan areas. Those with cancer, middle disease, and stroke were excluded at the showtime of the study. Coffee consumption was assessed once at the kickoff of the study.

- About 52,000 people died during the form of the report.

- People who drank between two and v cups of coffee daily showed a lower hazard as well, just the amount of reduction increased for those drinking half dozen or more cups.

- The sample sizes were adequately large so the p-values are quite small, even though pct reduction in risk was not extremely large (dropping from a 12% chance to about 10%–11%).

- Whether java was caffeinated or decaffeinated did not appear to affect the results.

- This was an observational study, so no cause-and-consequence conclusions can be drawn between coffee drinking and increased longevity, contrary to the impression conveyed by many news headlines about this study. In particular, information technology's possible that those with chronic diseases don't tend to drink java.

This study needs to exist reviewed in the larger context of like studies and consistency of results across studies, with the constant caution that this was not a randomized experiment. Whereas a statistical analysis can nevertheless "adjust" for other potential misreckoning variables, we are not yet convinced that researchers have identified them all or completely isolated why this decrease in death risk is axiomatic. Researchers can now have the findings of this study and develop more focused studies that accost new questions.

Think It Over

- Find a contempo inquiry commodity in your field and answer the following: What was the primary research question? How were individuals selected to participate in the report? Were summary results provided? How strong is the evidence presented in favor or against the research question? Was random assignment used? Summarize the main conclusions from the study, addressing the issues of statistical significance, statistical confidence, generalizability, and cause and result. Do you agree with the conclusions drawn from this study, based on the report design and the results presented?

- Is it reasonable to use a random sample of 1,000 individuals to draw conclusions about all U.S. adults? Explicate why or why non.

Glossary

crusade-and-effect: related to whether we say one variable is causing changes in the other variable, versus other variables that may be related to these two variables.

generalizability: related to whether the results from the sample can be generalized to a larger population.

margin of error: the expected amount of random variation in a statistic; often defined for 95% confidence level.

population: a larger collection of individuals that nosotros would like to generalize our results to.

p-value: the probability of observing a item effect in a sample, or more extreme, under a theorize virtually the larger population or process.

random consignment: using a probability-based method to divide a sample into treatment groups.

random sampling: using a probability-based method to select a subset of individuals for the sample from the population.

sample: the drove of individuals on which we collect data.

Contribute!

Did yous have an idea for improving this content? We'd love your input.

Improve this pageLearn More

Source: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/waymaker-psychology/chapter/reading-drawing-conclusions-from-statistics/

Posted by: williamsherat1979.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Which Of The Following Help Readers Draw Conclusions Or Support Business Decisions?"

Post a Comment